Scientists at the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology have achieved what was once thought impossible, severing reproduction from fertilization.

In a remarkable feat, they have successfully created synthetic human embryos using stem cells, eliminating the need for sperm or eggs altogether, as reported by the Guardian.

These models were nurtured in nutrient-filled bottles, effectively serving as “a kind of crude artificial uterus.”

According to the Quanta Magazine, Professor Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz of Cambridge, along with Jacob Hanna from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, has been working diligently on developing mouse embryo models from stem cells.

These models were nurtured in nutrient-filled bottles, effectively serving as “a kind of crude artificial uterus.” Astonishingly, these synthetic embryos exhibited the development of crucial elements such as a spinal column, a nascent head, and even a primitive beating heart.

Simultaneously, a team of researchers led by Zhen Lu, a Chinese reproductive engineer at the State Key Laboratory of Neuroscience in Shanghai, accomplished a similar feat using monkey embryonic stem cells.

They successfully initiated pregnancies in monkeys through a process resembling in vitro fertilization. Inspired by these results, Żernicka-Goetz and Hanna embarked on their own exploration of primate embryos, determined not to be left behind.

“We can create human embryo-like models by the reprogramming of [embryonic stem] cells.” Żernicka-Goetz stated.

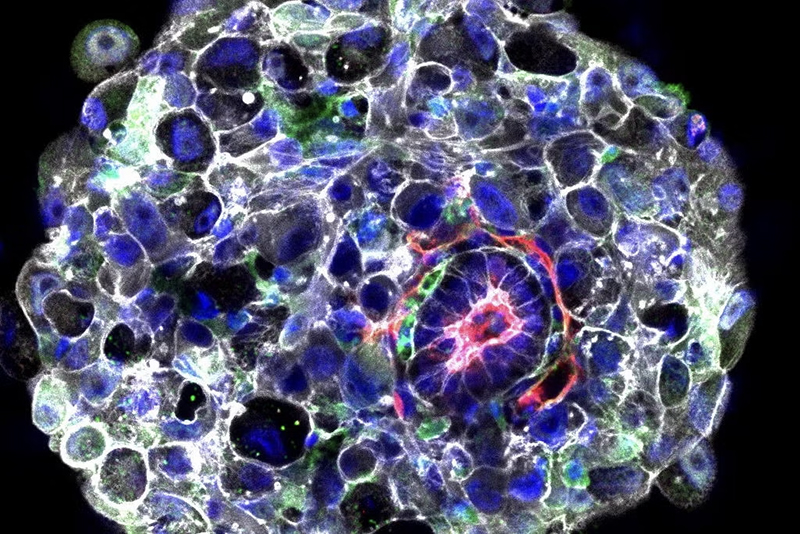

In a plenary address before the International Society for Stem Cell Research in Boston, Żernicka-Goetz unveiled her latest breakthrough. She stated, “We can create human embryo-like models by the reprogramming of [embryonic stem] cells.” These human embryo models have surpassed the equivalent of 14 days of natural embryonic development, reaching a developmental milestone called gastrulation.

During this stage, the embryo transforms from a continuous sheet of cells into distinct cell lines, establishing the fundamental body axes.

Although lacking a beating heart, a gut, or the beginnings of a brain, the models displayed the presence of primordial cells that serve as the precursor cells of egg and sperm, as described by the Guardian.

Żernicka-Goetz described the process and its outcomes as “beautiful” and emphasized, “Our human model is the first three-lineage human embryo model that specifies amnion and germ cells, precursor cells of egg and sperm.”

“Our human model is the first three-lineage human embryo model that specifies amnion and germ cells, precursor cells of egg and sperm.” Proclaimed Żernicka-Goetz

Janet Rossant, a developmental biologist and member of the International Society for Stem Cell Research steering committee, acknowledged the potential of these synthetic embryos to develop into viable humans if equipped with the necessary cell types. This raises profound questions about the nature of life itself.

Żernicka-Goetz clarified to CNN that these models are not human embryos but rather embryo models with striking similarities to their human counterparts.

She highlighted their significance in uncovering the reasons behind many pregnancy failures that occur during the developmental stage replicated in these structures.

The distinction between these embryo models and natural embryos lies in their derivation, according to Christine Mummery, a developmental biologist at Leiden University Medical Center. Unlike embryos derived through fertilization, these models are created using stem cells.

While implanting these embryos into a woman’s womb remains illegal, the stem cell-derived nature of these models offers scientists unparalleled flexibility compared to traditional fertilization methods. James Briscoe, associate research director at the Francis Crick Institute, stressed the urgent need for regulations governing the creation and usage of stem cell-derived models of human embryos, as the existing legal frameworks designed for in vitro fertilization embryos do not cover them.

The potential implications of these synthetic embryos are raising concerns among experts and policymakers alike.

The “14-day rule,” which restricts the in vitro culture of IVF-sourced embryos beyond 14 days, currently regulates the ethics surrounding such research. However, the International Society for Stem Cell Research recommended in 2021 that the possibility of extending this limit be considered.

NPR reported that the creation of embryoids, living entities made from human stem cells, has added pressure to extend the rule. Scientists seek to compare these embryoids with naturally conceived embryos, pushing the boundaries of the 14-day limit.

Dr. Ildem Akerman from the University of Birmingham urged caution, emphasizing that the ability to do something does not automatically justify doing it. As science ventures into uncharted territory, ethical considerations must remain at the forefront of decision-making.

The breakthrough in synthetic human embryos marks a pivotal moment in scientific advancement, propelling us toward a future that challenges our understanding of life and reproduction. The ethical implications are profound, demanding a delicate balance between scientific progress and the moral boundaries that guide our actions.